Palestine: A Socialist Introduction by Sumaya Awad and Brian Bean was an easy choice for me when looking to begin reading about Palestine and the Israeli settler occupation. I’m new to both Palestine and socialism, and the road of social justice seems to lead inevitably to both.

It’s hard to judge a book when it’s the very first you’ve read on a topic. I have nothing to compare it to. The only questions I had going into Palestine: A Socialist Introduction were whether it was what it claimed to be. Was it about Palestine? Was it socialist? And was it at an introductory level?

The book clears the first question with flying black, white, green, and red colors. It focuses on Palestinian liberation, with a necessary exploration of the political climate of surrounding Arab countries and parallels into anti-Black racism in the United States. It consists of nine chapters, several of which are reprinted essays and articles from various authors. Bookending them are an introduction and a conclusion by Awad and Bean.

The colony we call Israel

The first chapter, “Roots of the Nakba: Zionist Settler Colonialism” by Sumaya Awad and Annie Levin, immediately drew me in. The origins of the settler colony of Israel were entirely new to me, and the truth is more abhorrent than what I imagined. I learned that modern Zionism began not with the 1948 Nakba—which I also just learned about—but gained traction with Theodor Hertzl’s writings in 1896 after the Dreyfus affair.

The history of modern-day Israel effectively dispels any notion that anti-Zionism is anti-Semitic. In fact, the very existence of Israel is due to Hertzl and his contemporaries’ belief that “antisemitism was a permanent feature of human nature.” They proposed the unfounded “solution” of simply removing the Jews from Europe where they were being persecuted, instead of, say, actually fighting back against that racist hatred.

Awad and Levin go on to combat the idea that “the State of Israel is necessary to combat another Holocaust.” They shared example after despicable example of Zionist leaders saying things like,

The hopes of Europe’s six million Jews are centered on emigration. I was asked: “Can you bring six million Jews to Palestine?” I replied, “No.” … From the depths of the tragedy I want to save … young people [for Palestine]. The old ones will pass. They will bear their fate or they will not. They are dust, economic and moral dust in a cruel world … Only the branch of the young shall survive. They have to accept it.

Chaim Weizmann, the first president of Israel

Verifying this quote: a side quest

I always try to do my due diligence and authenticate quotes, especially detestable ones like this. In Palestine: A Socialist Introduction, the bibliography states only that this was pulled from another book in which it was also quoted, Ralph Schoenman’s The Hidden History of Zionism. Schoenman himself was quoting from another book, Faris Yahya’s Zionist Relations with Nazi Germany. Yahya’s book cites vaguely, “Statement to Zionist convention in London, August 1937.”

I thought at first that Yahya’s cryptic citation led to a dead end. Not one to give up, I found that the Zionist convention in August 1937 was actually the Twentieth Zionist Congress, part of the Peel Commission. The Congress was where British and Jewish Zionists discussed a “partition plan” for Palestine, similar to what some today call a “two-state solution.” The quote comes from one of the addresses that Weizmann gave there, but as one helpful blogger noted, “Weizmann’s remaining four testimonies were all given privately, and were correspondingly more candid. . . . Weizmann’s private testimonies survive only buried in his personal papers.”

Finally, that blogger’s reference list took me to The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann, Series B, Vol. II, page 283. The full quote (translated from the original German into English), which I have not found anywhere else on the internet, reads,

I told the Commission: God has promised Eretz Israel to the Jews. This is our Charter. But we are men of our own time, with limited horizons, heavily laden with responsibility towards the generations to come. I told the Royal Commission that the hopes of six million Jews are centred on emigration. Then I was asked: ‘But can you bring six million to Palestine?’ I replied, ‘No. I am acquainted with the laws of physics and chemistry, and know the force of material factors. In our generation I divide the figure by three, and you can see in that the depth of the Jewish tragedy: two millions of youth, with their lives before them, who have lost the most elementary of rights, the right to work’.

The old ones will pass, they will bear their fate, or they will not. They are dust, economic and moral dust in a cruel world. And again I thought of our tradition. What is tradition? It is telescoped memory. We remember. Thousands of years ago we heard the words of Isaiah and Jeremiah, and my words are but a weak echo of what was said by our Judges, our Singers, and our Prophets. Two millions, and perhaps less: Sche’erit Hapleta — only a remnant shall survive. We have to accept it. The rest we must leave to the future, to our youth. If they feel and suffer as we do, they will find the way, Beacharit Hayamim — in the fullness of time.

Chaim Weizmann, Plea to Accept Partition Plan, Address to Twentieth Zionist Congress. Zurich, 4 August 1937.

Yahya’s book had said that the quote was from a convention in London, not Zurich. But with so much of it the same, I believe that this is the quote that ultimately ended up in Palestine: A Socialist Introduction. (Unless Weizmann uttered the same quote more than once—which can happen.) Perhaps the more cut up sections are due to different ways of translating the original German, or, of course, making the quote sound more comically evil than if one were to read it in whole.

I’m disappointed that the authors merely told us where they found it, rather than trying to determine where this quote originally came from. I was able to find it after a couple hours of Googling while writing a book review, but they did not when writing an actual book.

Back to Palestine: A Socialist Introduction

The first chapter had me hopeful that the book would be a worldview shaper, but the rest was less gripping. While it was definitely Palestine, and it seemed socialist to me, it was not introductory. Maybe the information was basic and obvious, but I truly needed a total beginner’s guide—like, progressive white girl from Pittsburgh who was raised in a colorblind sheltered Christian bubble, level of beginner.

For example, chapter 3, The National Liberation Struggle: A Socialist Analysis by Mostafa Omar is a reprint of an essay from the 2002 Haymarket Book The Struggle for Palestine. That tells me that this chapter was not written explicitly to be introductory, and it shows. It begins,

Since the Oslo Accords were signed in 1993, endless rounds of negotiations between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Israel have failed to secure an end to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, a Palestinian state, or the right of return for five million Palestinian refugees.

Mostafa Omar, The National Liberation Struggle: A Socialist Analysis

Omar assumes that his readers know what the Oslo Accords and the PLO are. He discusses them at length without ever truly breaking down his terms for the uninitiated, which—in an introduction—would be everyone.

Almost every chapter went over my head. When the authors aren’t discussing events with the assumption that their readers have already studied them, they are using advanced political language that the everyday reader would struggle to grasp.

Palestine: A Trotskyist Introduction

My frustration about the book’s advanced level is nothing compared to other socialists’ critiques that the book is not operating from a responsible socialist framework. I first became aware of this through this tweet thread from Louis Allday, as it’s been discussions of the book across Instagram and Goodreads cite it. (There was a comment referring to the tweet thread on that Instagram post, but Haymarket appears to have deleted it.)

Louis writes in the thread, “Putting both ‘Palestine’ and ‘Socialist’ in the title AND giving it away for free is the perfect way to get enormous numbers of well meaning people to read ahistorical, counter revolutionary, anti-anti imperialist lies packaged in leftist language. It’s very concerning,” and “using this moment, when so many people are desperate to learn more about Palestine and support it, to spread propaganda demonising enemies of the US is extremely low.”

I’d like to think I’m one of those well-meaning people who’s desperate to learn more about Palestine. That’s why I read this book. I was alarmed to see that the book is “*full* of Trotskyist/State Dept lies about socialist states,” “full of attacks on the ‘Stalinist left’,” “full on reactionary propaganda in leftist language.”

If the book is that bad, I’m glad I know. But when reading it, I had no idea there was anything wrong with it. Much of the criticism was that the book is Trotskyist. Do you think Grove City College taught me what Trotskyism is? (The answer is no.)

It is full of attacks on the “Stalinist left” and anti-imperialist states/movements and it makes absurd, false and irrelevant claims about enemies of the US. Such as this: “Cuban workers and peasants did not take part in making the revolution”. pic.twitter.com/AE77Uv3zr0

— Louis Allday (@Louis_Allday) May 11, 2021

Who to trust?

Random commenters on Twitter aren’t obligated to explain basic terms to me, but it’s frustrating to be repeatedly led to this specific thread of folks who seem righteously angry about something. I’d love to make an informed opinion on whether this book is full of lies and whether its publisher Haymarket Books, truly is “a trot org.” I’m simply not getting any information. One of the comments led to this article, which is staunchly against Haymarket Books, the Democratic Socialists of America, and Jacobin Magazine, all of which came together to create the 2019 Socialism Conference.

As much of the extremely long article as I could make it through focused on condemning the conference’s anti-China stances. I gave The Grayzone the benefit of the doubt, but the tone of the article didn’t feel right. The panels, speakers, and groups they criticized seemed totally normal. The Grayzone‘s Wikipedia page waves more explicit red flags:

It is known for its critical coverage of the US and its foreign policy,[1]misleading reporting,[25][26] and sympathetic coverage of authoritarian regimes.[4][21][27][28]The Grayzone has downplayed or denied the Chinese government’s human rights abuses against Uyghurs,[32] published conspiracy theories about Venezuela, Xinjiang, Syria, and other regions,[33][34] and published pro-Russian propaganda during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[31]

The Grayzone – Wikipedia

Again, I could be wrong. All I have to go on so far is my gut, but something doesn’t feel right. If this article is from a misleading conspiracy theory website, could that be the viewpoint of most of the people in the thread criticizing Palestine the book?

What is Trotskyism?

My natural next step was to try to learn what Trotskyism is. Well, you can’t actually just Google “What is Trotskyism?” All you’ll find is that Trotsky was against Stalin. I dared to ask on Reddit, where folks were actually pretty kind and patient.

One person told me, “Listen carefully. This subreddit is intensely Marxist-Leninist and they are completely opposed to Trotskyism. You will get one side of the argument here. Don’t have this sub be your only source when making a conclusion,” to which someone replied, “For the OP’s point, I think it’s really a matter of pragmatism and methodology. Different schools of thought allow a certain tolerance of good before it becomes the enemy of perfection.” I appreciated that they took the time to respond, but they didn’t answer my question.

One Trotskyist commenter did their best to explain the central questions answered by Trotskyism to me in under 400 words, but even that would require a solid understanding of the USSR and its civil war to make a good amount of sense.

The best answer? “Trotskyism is basically the idea that you can’t build ‘socialism in one country’ but rather there must be a ‘permanent revolution’ that spreads globally. Trotskyists, on their terms, therefore, don’t view any actually existing socialist countries today as being legitimately socialist and refer to them as countries which ‘regressed back into capitalism’. As a noob to socialism I would advise you avoid this particular squabble. You should develop a better theoretical basis for your own thoughts first by reading Lenin, Marx, Engels, Luxembourg, etc.”

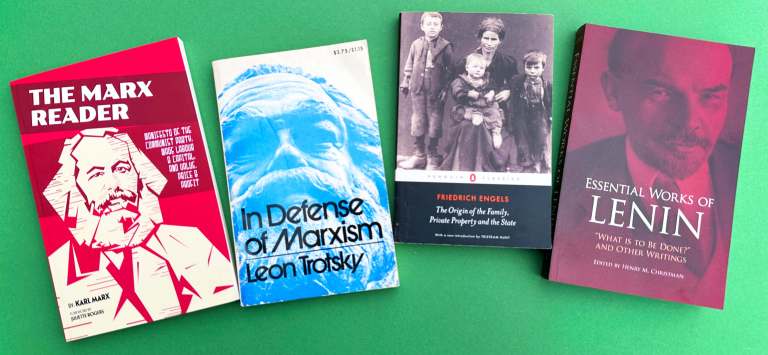

Essentially, the answer was to get off the internet and read a book. (Which is ironic since reading a book was what led me to the internet. This is why I have so many books. It never ends.)

More questions than I started with

All this to say, I can blame Palestine: An Introduction for my burgeoning quest to read as many primary sources on communism and socialism as my brain can handle. I don’t like having no idea what’s going on.

Fortunately, one Redditor pointed me to an article called The Palestinian Left Will Not Be Hijacked – A Critique of Palestine: A Socialist Introduction, which seemed less unhinged than the last. Once again, unsurprisingly, most of it went over my head. This is due to a mixture of its density, academic tone, and the fact that I have virtually no background on anything it’s talking about. I gleaned that Samar Al-Saleh and L.K., the article’s writers, take issue with Amad and Bean’s conflation of Palestinian nationalism with nationalism in imperialist, capitalist countries. They defend the PFLP’s Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine from Awad and Bean’s accusations that the PFLP was “Stalinist” and “regularly manipulated by the Soviet Union.”

Palestine: A Socialist Introduction taught me that maybe there is no way to be gently introduced to either Palestine or socialism. It didn’t help me understand much. Rather, it gave me dozens of new questions, fueled by socialist “squabbles” that I didn’t even know people were having. The best I can say is that it told me what I didn’t know, and what I need to learn. Needing to read stacks of books in order to make an informed opinion is a challenge I’m eager to take on in 2024.